Climbing is for the strong.

The most common response I hear when I ask a friend if they want to try climbing is, “I’m not strong enough.” When I met Brian, my for-awhile-now life-partner-in-crime-and-climbing, I already knew he was a rock climber. At that time, I absolutely was not. I was the opposite of a rock climber. I was a non-athlete. Indeed, I may have been an anti-athlete. If there was anything I was remotely sporty about, it was smoking cigarettes— at that, I was a champ. Even though by the time I met Brian, I’d already quit that terrible habit and wanted to be less floppy as a human being, it still took him a long time to convince me to try climbing at The Climbing Wall where he worked part time. I wanted to climb, but I was so worried that I wasn’t going to be able to do it. I was so worried that I wasn’t strong enough, that I was going to look like a fool. He practically had to drag me there— but it ended up that I could do it, and did do it. Maybe at first I looked like an awkward newby, but it clicked with me in my mind and body, even though I had no muscles whatsoever to speak of.

I learned almost immediately that climbing is a sport, or rather an endeavor, that meets you where you are— I’ve said it before. Any person of almost any age and ability and strength— or weakness— can find something to climb at their very own level. I don't mean that climbing won’t feel hard. Climbing will feel very hard, especially at first. At first, you might only be able to try one or two routes or boulder problems, and you might not even get to the top. You might fall. You might look a little silly— everyone does at the start. You might end up with extremely sore muscles and skin because you’ve never used them that way.

Climbing might even reinforce that you are weak most of the time, or maybe I should say, it may make you feel like you’ll never be strong enough. You can let that overwhelm you, and you can quit before you even get started. Or, you can let it intrigue you. And the more you climb, the less it will hurt, the less it will feel overwhelmingly difficult, and perhaps, the stronger you will feel. Sometimes.

Here is a great short video showing how people at very different levels can climb together!

Climbing is for people who can do pull ups.

This is related to the strength myth, but it is one I think worth tackling by itself. When someone says to me they aren’t strong enough, they usually follow it up by saying, “I can’t even do a pull up.” There are probably more climbers than you think who cannot do pull ups. Maybe they can do one pull up, but maybe not even one. Maybe more like half of one. But I don’t know anyone who posts on the socials about their inability to do a pull up. Most people only post about what they are good at, what they can do. Being able to do a bunch of pull ups does not necessarily convert to being good at climbing. I could not do pull ups when I started climbing. I climbed regularly for months and months and months, maybe even a year, before I could even do one with difficulty and terrible form. I’m not the best climber— a million other people have always been stronger and better at climbing than me— but I am successful at it on my own level.

While it seems like climbing is focused on the upper body, it actually requires all of it— leg muscles are just as important as arm muscles, toes and feet are just as important as fingers and hands. Sure you might see somebody in the gym (or on IG) campusing (only using their arms) up a climb, and that could be good for training strength. It could be a good way to hurt yourself if you’re not ready for that exercise too. But if you learn how to maximize the use of your legs, feet, toes, it will ease the load on your arms, shoulders, hands, fingers. It could save you from injury. And don’t forget your core. Core muscles tie the whole package together. The ability to engage your core may actually be the most important kind of strength for rock climbing.

Ironically though, if you start climbing, and you keep it up regularly for a while, you may just end up being able to do pull ups. So if you want to be able to do pull ups, start climbing and see what happens.

Climbing is for the kids.

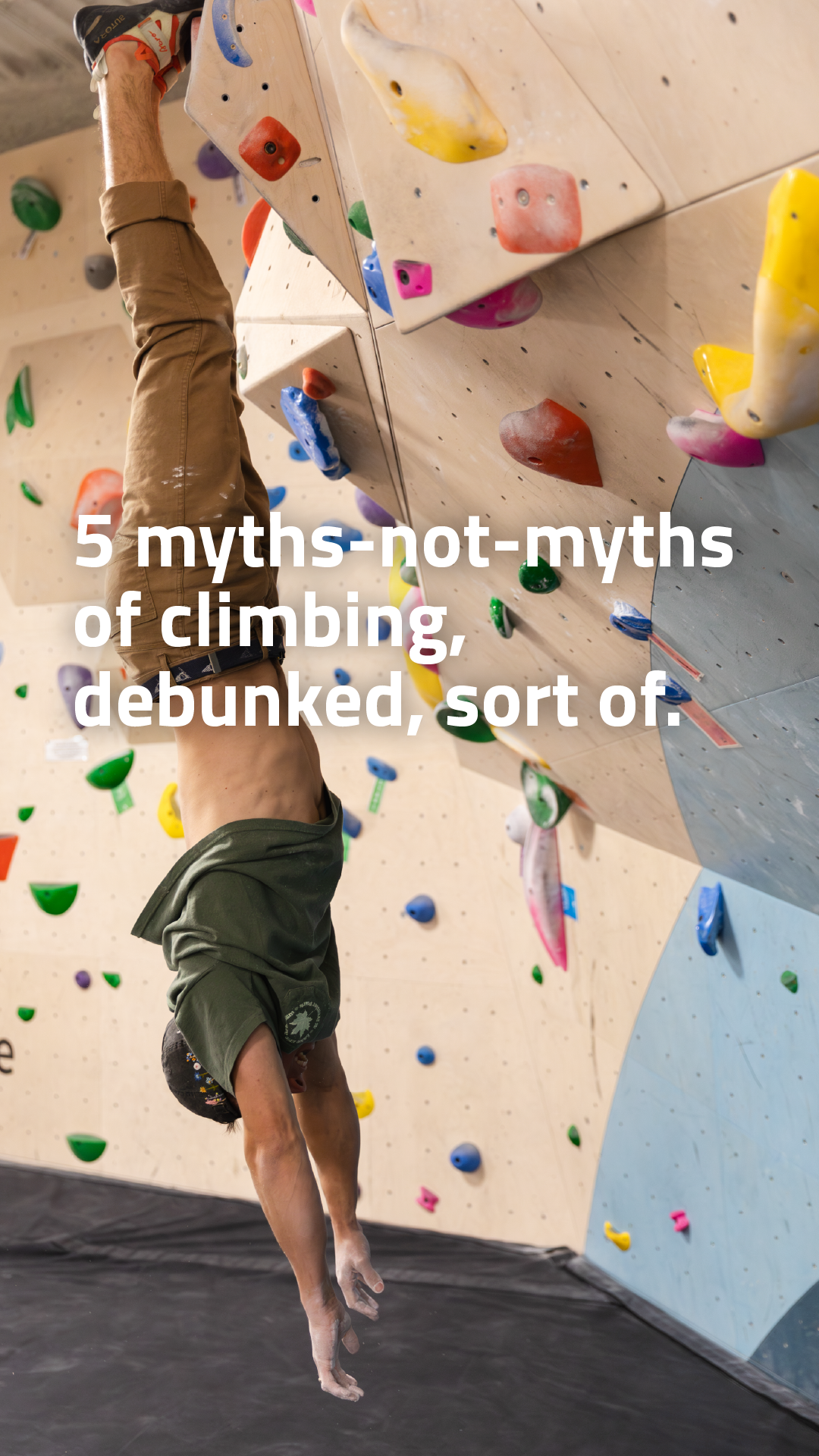

Maybe you think climbing is childish. The gym is colorful and looks like a playground of sorts, sure. But rather than saying climbing is for the young, it should be said that it’s for the young at heart.

If you look around the climbing gym, more than kids, you will see adults of all ages, and you might even notice a growing number of old(er) folks, the gray-haired ones. That’s because climbing tends to be an activity that you can continue to partake in even as you age. It’s something that you keep doing over the years and perhaps, just perhaps, it keeps you young.

I started climbing as a 20-year-old— some people might have called me a kid even at that age— but now as a 51-year-old it’s still with me. I climb at whatever capacity I can. I’ve written about that before here, here, and here. It’s the way I “play,” even if that means I’m very serious about it. I believe playing is an important thing to do at every age and stage of life; playing is also not just for the young. It’s good for humans to play using their body and their mind together.

There are some climbers at the gym who are older than me and have been climbing longer. If you ask them, they may tell you that climbing keeps them young too— at least young at heart, if not in body.

Climbing is too expensive.

Yes, climbing can be expensive. This is not really a myth. However, climbing is something you invest in, paying an upfront cost that over time can render it cheap(er). You’re investing in, not only the sport itself, but in your own overall improved well-being.

If you decide to climb outside on your own, the upfront costs are for gear— your own stuff and things: shoes, chalk bag, crash pad if you are going bouldering; rope, harness, sport or trad equipment for route climbing. Bouldering is the simplest version of climbing and therefore the cheapest.

I’d say, climbing shoes end up being the thing that climbers spend most of their money on. Shoes are expensive new, and you can resole them a few times, but often climbers wear out a pair and then buy a new one. I go through multiple resoles every year and possibly a new pair of shoes every 2-3 years. I am also very picky about what kind of shoe I climb in, what works best for me on the wall. I have an inside pair and an outside pair.

You used to be able to get a moderate-level performance model for around $100, but now prices are pushing $150-200. To waylay this high cost, you can sometimes find used shoes at Three Rivers Outdoors in Regent Square or REI in the South Side. There are also websites for discounted outdoor gear like sierra.com if you know what you are looking for. ASCEND gyms have occasional shoe demos with Evolv and Butora, and if you decide to buy a pair during one of these events, you usually get a discount. Also check out the bulletin boards at each gym location where climbers regularly post ads for shoes they want to sell.

The rope is another item that has to be replaced somewhat regularly if you climb often. Ropes are over $100 new, and are not something you’d want to buy used— same with harnesses and usually trad gear. It’s important to know the history of any of these products— it’s better that these don’t have a history, unless it’s your own. Your rope will last longer if you care for it well, regularly cleaning it, storing it in a dry place, and using both ends. And you need to pay attention to how it’s wearing if you take a lot of falls on it.

Your climbing harness and gear (quickdraws or trad gear, or both!) will last you years, sometimes decades without having to replace them completely. Again, it’s how you take care of them. You may dump a chunk of change on a new rack of trad gear and/or quickdraws, but you can also start small and build it up gradually. Brian and I have bought used quickdraws and trad gear from friends who decided to quit climbing. We knew these friends well, and knew how meticulous they kept everything they owned, so we decided that it would be okay in this case. Decades later, we’d still be using that trad rack if it wasn’t for our van fire. Damn— I guess the lesson there is, don’t leave your gear in your car when you aren’t using it.

Many people don’t know about grants and scholarships offered by climbing/mountaineering organizations, both national and local, for gear, trips, and education for outdoor climbing. Both the American Alpine Club (AAC) and the Southwestern PA Climbing Coalition (SWPACC) offer funding support for adventurous folks of all kinds and ages. I didn’t know this was a thing until one ASCEND family’s six children each received a Live Your Dream grant from the AAC to help fund a summer climbing trip a few years ago. Each one had to apply and state a climbing goal they wanted to achieve, and then write a story about it at the end of the trip. This also led to these kids starting their own podcast.

Climbing at a gym is more expensive than climbing outside— you have to pay to play— but there are ways to lower the cost. If you want to climb regularly at the gym, buying a membership is a way to lower the daily rate. At the ASCEND gyms, a month membership (after an initiation cost) is $85— student, senior, and various other discount memberships reduce the cost even more. Don’t forget that the ASCEND memberships are all inclusive. Not only do you get to climb all day, at all their locations, you also get yoga AND fitness AND slackline classes, as well as discounts on gear, other classes, and much more.

ASCEND desires equity for every person who wants to climb in the gyms, so they do offer a robust Financial Assistance program for those who qualify. This assistance extends to the programs ASCEND offers in the gym (youth camps and teams, classes, etc.) as well as outdoor climbing opportunities, gear rental, and transportation to certain special events.

Climbing is not safe.

There is a necessary disclaimer we see and hear all the time: Rock climbing is a dangerous sport that can lead to injury or even death— whether reading it on a waiver that we sign at an indoor climbing gym, or seeing it on a sticker in a book about climbing that we check out from a library, or hearing it from the mouths of those who have taught us to love this activity: Climbing is dangerous.

Indeed, climbing is absolutely dangerous in many ways. Whenever you talk about an activity involving height and gravity and the possibility— no, the inevitability— of falling, said activity will immediately be labeled as dangerous. Falling can hurt you, and if you fall far enough or wrong enough, falling can be deadly.

I think a lot of people who aren’t familiar with rock climbing wonder if ascending a wall, whether outside on real rock or inside on plastic, is even a natural thing for human beings to do. Should humans climb? Seems silly. Seems a little crazy. People who climb must have a death wish or are a bunch of adrenaline junkies, right?

Before I ever tried climbing myself, I would have said, only crazy people climb rocks. And this may be true about a small population of climbers. But when Brian taught me how, I realized that it’s much safer than I could ever have imagined without trying it myself. In some small sense, the amount of danger we want to contend with is under our control. As climbers, we can decide which risks we are willing to encounter. To me, climbing is waaaaay safer than momentum sports like mountain biking or skiing/snowboarding or maybe even tennis.

Climbing in the gym is extremely safe, as long as you follow the rules, as long as you use the safety gear properly, as long as you are thoughtful and pay attention. Take the belay class. Take the lead class. Listen closely to the instructor when they tell you the rules. Be receptive to constructive criticism if they tell you you are doing something wrong.

Bouldering is a bit more dangerous than climbing on a rope. Even though you do climb above and fall onto thick mats, it is possible to fall wrong and injure something. Climbing on ropes, however, adds another level of safety gear, and therefore another level of knowledge and paying attention. Instead of worrying about your own self, as a boulderer does, when climbing on a rope, you are part of a team, and your partner’s life is in your hands. Now you have to worry about their safety too, and you have to trust that they are concerned about yours.

Climbing outside is a less controlled arena than the gym, but it can still be safe. Bouldering relatively close to the ground using crash pads carries with it the possibility of injury, but it really depends on the climber and the ground. If the climber is confident and strong enough to do whatever the problem is they have chosen and the ground is somewhat level, it is unlikely that injury will occur. If a climber is confident in their ability, these boundaries can be safely pushed. In my own experience, while I broke my ankle in the gym falling from a relatively low height, I have fallen off of, without injury, and later reached the top of a 25 foot tall boulder outside.

Route climbing outside introduces more risk as it is up to the climbers to set up the rope at the top of a cliff line. Because there are many points in the process of fixing the rope safely to the top that can be affected by human error, route climbing may seem like a more dangerous choice. However, if you climb with people who know what they are doing— are experts of a sort— or if you are adept and cautious in following each step, you are very likely going to be very safe.

Of course, as I mentioned before but is worth repeating, there is the possibility of the occasional freak accident when a route can’t be well-protected with safety gear, or the safety gear itself fails, or there is rock breakage. Due to the law of gravity, falling from a height to the ground or getting hit by a falling rock is very hard on the human body. This cannot always be prepared for, so it is important that we all become and remain aware of the risks.

Climbing is dangerous, but it can be safe.